To prune or not to prune – this is an important question to ask in late fall as we prepare our gardens for winter.

Jump to: Pruning Perennials | Pruning Woody Plants | Timing

Cutting Back Perennials

I don’t think of cutting back perennials as pruning, but whatever you call it, Fall is a good time to proceed with this task if you haven’t already done so.

I leave perennials that have sturdy stems and full seed heads to provide some winter interest, help hold snow in place, and feed birds whose food sources are rapidly diminishing.

By contrast, I cut back plants that are flattened by snow and get messy when they thaw (a good example is day lilies).

In contrast to woody plants, most of those we call perennials are herbaceous, putting out all new growth each spring.

Exceptions include some vines (for example, some varieties of clematis bloom on old vines) and plants like Russian sage, which is classified as a subshrub and puts out new growth on old branches.

To know which is which, keep a list of the botanical names of your plants or save the tags that were in the pots and look them up if you’re uncertain about what to do.

Pruning Woody Plants

If you’re considering pruning anything woody, proceed with great caution. Specific weather conditions, plant types, and plant health or conditions are elements to consider.

Specifically: Don’t prune anything that blooms on old wood. If you look at your lilacs or azaleas, for example, you’ll see that they have already set buds for next year’s flowers. If you prune those branches now, you’ll get nothing but leaves next year.

However, flowering shrubs that bloom on new wood (like shrub roses and some hydrangeas) will still flower next year if pruned now.

Don’t prune anything that is still actively growing. If you do, you risk stimulating new growth that will be more susceptible to damage from winter freezing.

Complete leaf drop is generally a measure of dormancy, but if in doubt, wait until mid-winter to prune trees and shrubs (February is often suggested as a good time to prune).

Like any good rule, there are exceptions to the guidance above. If a shrub or tree has any damaged or broken branches, it can be a good idea to remove them before snow or ice can cause more damage.

Damage can result, for example, if the weight of wet heavy snow tears a branch off, pulling down the bark and exposing the tender inner layers important to the health and growth of trees and shrubs.

Regardless of what or when you prune, be sure to use tools that are clean, sharp, and appropriate for the task at hand. Keeping your pruners clean will help eliminate cross-contamination from diseased to healthy plants.

Sharp blades help ensure clean cuts and reduce the likelihood of torn bark. And use of a proper tool will help ensure that you’ll get a good result that might not be possible if, for example, you try to use too small a tool for the task (which can also damage the tool).

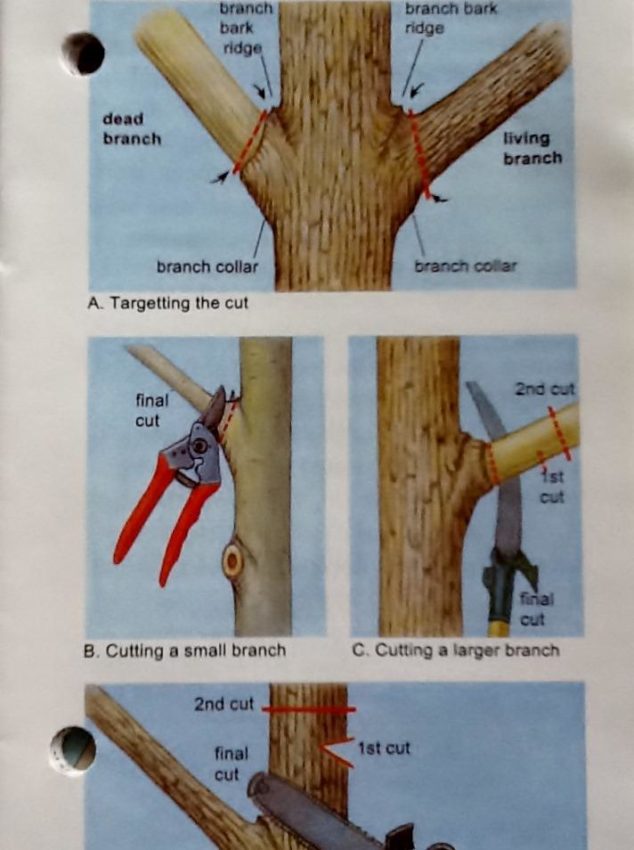

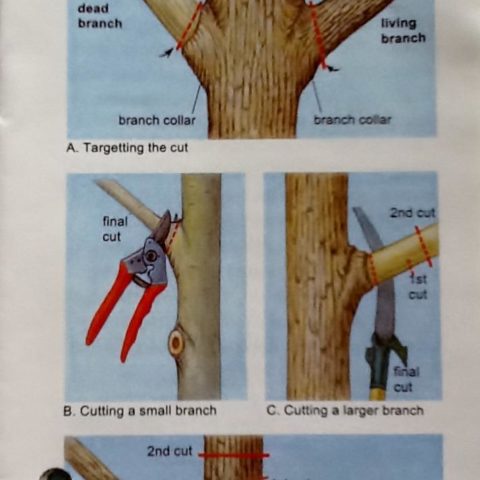

When you do prune, do a little research first so that you know how much to prune and where to make the cuts. For example, the correct cut will generally be made at a 45 degree angle (a steeper angle leaves more exposed surface that can, for example, allow easier entry of disease).

Patterns of branch growth on a shrub or tree can help you determine where to prune in order to get the shape or size you desire or to “open up” a tree or shrub whose branches have become too dense. Lots of good photos and drawings are available on extension websites (a good site is University of Minnesota’s Extension Service website), other gardening websites, in free government brochures, and in books at the library.

A Few Last Words on Pruning in Late Fall

If, after a bit of research, it seems wise to proceed, do so carefully and remember that there are worse things you can do than to prune something earlier than you should.

If you prune a lilac now, for example, you may miss those beautifully scented blooms next year, but you may end up with a nicely shaped shrub that will reward you handsomely another year out.

On the other hand, you don’t want to jeopardize a mature tree or special shrub that won’t be easily replaced. So if you are in doubt, just wait.

While we sometimes learn best from our mistakes, some outcomes are just too costly to justify the risk. Here’s where the cliche is true: better safe than sorry.

If you like my articles about cooking and gardening, subscribe to my weekly newsletter, where I share free recipes and gardening tutorials.

Leave a comment